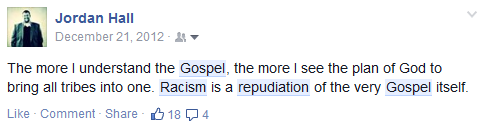

“Things are about to change. It’s show-time.” – Todd Friel

Todd Friel joined me for breakfast on June 26, and broke from conversation long enough to check his phone. He received a text message that the Supreme Court had spoken on the issue of gay marriage. He, myself, and another brother at the table were mostly devoid of emotion. It was a foregone conclusion. We knew that. We knew the day had come. And Todd was right. This changes things.

Oh, the Supreme Court didn’t change everything. Marriage is still an institution created and defined by God as between a man and woman. God is still sovereign. Our liberty to speak prophetic truth to a dying culture is still in place (and will be even after they find a way to legislate against it). But like it or not, things are changed.

Most of the day was devoid of emotion. I asked the speakers of the 2015 conference – even after a very long day of preaching on the topic of the Church – to hang in there for one more late-night roundtable discussion on how the church should react to the ruling. Even that discussion was devoid of emotion, unless deflated is an emotion.

My father sent me a photo of the flag in his front yard, lowered to half-mast with the caption, “I’ll never raise her again.” When I got home, still numb to it all, I lowered mine, too. Like my father, I’ll never raise it again. I’ll also not take it down. I’ll leave it at half-mast forever. I’ll explain why in a moment.

Emotion didn’t hit me until last night. I dutifully prepared a sermon late Saturday night and early Sunday morning from Psalm 2. Mike Abendroth brought up the Text, and Phil Johnson mentioned that he would preach from it on Sunday. So did the Squirrel – a contributor to this website and fellow Reformation Montana board member. I figured I’d follow suit. My people needed to hear about how the church should respond to this ruling and how our elders would guide the flock in light of it. I also read for them a statement we prepared last year, when Montana was forced to redefine marriage thanks to the judicial activism of a liberal judge. I didn’t have time for emotion. I only had time to process the change, contemplate what was spoken at Reformation Montana, and prepare a sermon.

My emotion came when I went for a drive on an old dirt road out on the prairie, which is my usual Sunday night routine; that’s how an introvert like me gets alone and processes thoughts, feelings, and emotions. I was alone with just my God and my [super manly] station wagon. It was there that I felt it…anger.

- Did the President of the United States really just sing Amazing Grace and a funeral, while lighting up the people’s White House in rainbow colored lights?

- Am I really seeing virtually every major corporation in America change their logos to show gay pride (if there was ever a decent term to describe the hubris of man’s rebellion, that’s it).

- Did five Supreme Court justices really just take it upon themselves to redefine an institution created by God?

- Did a supposedly conservative justice really just decide that the Constitution was a living document that is to be interpreted in light of culture and not the authors’ intent? Because if so, I thought, “we’re done for.”

Anger. Anger is what I felt. Combine this with what’s occupied Pulpit & Pen’s time over the last week. Evangelical leaders have been focusing on a flag instead of sin and Gospel because repudiating symbolism garners cheap applause. Even the document put forward by the ERLC uses terms from the homosexual lexicon – LGBT – and lectures us to not be “outraged.” And upon that lecture, I’m even more outraged. I’m outraged that I’m being told not to be outraged.

I grew up in the Ozark hills, which was Yankee territory during the Civil War. While Missouri was a neutral state, the poor hillbillies in the Ozark hills didn’t appreciate the rich delta farmers profiting from cheap labor, and they often chose a guerrilla warfare-type resistance to the Confederacy. Both sides of my family came from north of the Mason-Dixie. And yet, in spite of historic realities, it wasn’t uncommon to see the “Stars and Bars” flying above the homes of neighbors (or more common, from the front license plates of pickups). So far as I know, there was one black kid in my entire county, and I was friends with him. I don’t remember any overt racism. There was nobody to be racist towards. I remember my grandmother admonishing my brother and I not to use a certain n-word toward black folks (not that we did). Racism, in those hills, was relatively absent. Hill folk have a pretty generous constitution; leave alone and be left alone.

I headed off to Arkansas for college, where I married an Arkansas girl. On the Mississippi delta, I saw racism for the first time. I remember driving all over my college town during all times of night my first summer away from home, without the second glance of any policemen. And, I remember being pulled over each time I took my Kenyan friend for a ride later in the school year; you know, polite questions from the police to ask what we were doing in the neighborhood. I was a teenager, but I knew what was going on. When moving to Jonesboro Arkansas, I saw self-segregation for the first time. Black folks had their neighborhood. White folks had their neighborhood. And oddly, I saw that both neighborhoods flew Confederate battle flags. I remember meeting a very, very old black man named “Mr. Cornelius” near Lake City who farmed the same patch of cotton ground his father share-cropped and his great-grandfather worked as a slave – and over the residence flew a Confederate battle flag, proud as could be. Then one night, racism came to my front door.

Living near the downtown area, my neighbors were white folks – one was an attorney, one was an accountant, a professional golfer, and so on – and a few blocks down the street it turned into a “black neighborhood.” My home was on the line between the two. One night, we heard screaming on the front porch. A group of black kids had wrangled a white kid on my front porch, and the victim was shouting, “Help! They’re trying to kill me!” A rack of my shotgun later, and I discovered the band of assailants were trying to force toilet bowl cleaner down the other’s throat. Oh, but racism came from both sides. In nearby Clay County, a black man had been beat nearly to death for dating a white woman – and the law enforcement wasn’t exactly eager to prosecute the offenders.

And yet, I don’t remember the Confederate battle flag being a point of contention. In fact, I put the flag on the front bumper of my pickup (complete with the gun rack in the back glass just for style). I would regularly pull into the heavily-diverse Arkansas State University among a gaggle of friends from all the colors of the rainbow. I don’t remember any of my black friends taking issue with the license plate.

And yet, I took it off. I took it off because my pastor pointed out that someone might be offended by it and they might assume I was a racist. “It will hinder your Christian witness,” I was told. I took it down, and didn’t lose any sleep over its loss. After all, if my NRA sticker and Bush bumpersticker couldn’t identify me as a redneck, nothing would.

I flew the flag so many consider evil, and removed it when it was suggested that it might be a barrier to the Gospel. I don’t think I’ve treated my black friends or my black brother-in-law, niece and nephew any different on account of their skin color, and I don’t think they’d treat me any differently if I still had that flag. But I don’t. And…I get it.

Racism is evil. Racism is wicked. Racism is contrary to the Gospel. Racism is demonic. I have reiterated over and again in my ministry that racism is wicked and – even though controversial in a few of the pulpits I’ve preached – I’ve taught that interracial marriage can be a beautiful picture of what God is doing through the Gospel to bring all tribes and nations into one.

And yet, while the Confederate flag is being repudiated by some who refuse to remove the names of slave-holders from their Baptist institutions, the head of ERLC is praising Obama for singing Amazing Grace on the same day he lit up the White House like a big, gay rainbow. Forgive me if there’s an altogether different flag I have a beef with.

About 12 million slaves were shipped across the Atlantic during the slave-trade. Of those, upward estimates are that 20% may have died in transit. About 90% of those never came to what is now the United States, but to South and Central America. By 1825, due to the conditions being “better” here than there, about 25% of slaves in the New World were in the continental United States (slaves typically died before reproducing in South and Central America, and typically did not in the United States – with a birthrate over 9 children per mother – leading to a population higher than proportion of import). And of those African descendants in 1860, about 90% were slave and 10% were free. The total number of slaves just prior to the Declaration of Emancipation was about 4 million.

Liberty was taken from – estimates indicate – upwards of 6 million men, women and children from the time the first African slaves arrived in colonial America and the end of Civil War. Millions died crossing the Atlantic. Many more died early deaths and were traded like cattle. It was atrocious. It was awful. It was sinful. And because of that legacy – even though the Confederate battle flag represents far more than advocacy for slavery, people argue it should come down. I completely understand the sentiment. That flag represents, in part, a denial of life and liberty to a great many people who were endowed by their Creator to have it.

And yet, the American flag waves on.

Since 1973, Americans have murdered nearly 55 million of our own infants. We’ve invaded the womb and murdered people made in God’s image, being knit together in their mother’s womb. We’ve made the American womb a more hostile and dangerous place than West Africa during the slave trade. A soldier in Iraq and Afghanistan have a greater chance (far, far, far greater chance) of escaping with their life than an infant in an American womb. We’ve made the womb to be most dangerous place in America.

And on the 26th of June, we’ve given God the middle finger of rebellion, telling Him that He has no right to govern our affairs. Our leaders have painted with lights our monuments with the symbolic colors of sodomy. We have profaned the institution of marriage. It just struck me today that this happened on my brother’s wedding anniversary. And then, again, I become angry.

Russell Moore says I shouldn’t be outraged. I am. I just…am.

Should I pledge allegiance to a flag that is easily as wicked – if not more so – than the Stars and Bars?

Should I utter, “…under God” in that pledge, when that is entirely untrue?

Should I sing, “God bless America” and bear false witness against the Bible’s promise of coming judgment?

Should I stand when the National Anthem is sung?

Some would argue that the Stars and Bars represents a nation that no longer exists, so there’s no point in displaying it. I agree. I would also say the same of Old Glory; it represents a nation that no longer exists.

While the flag in our church sanctuary was quietly removed, the flag in my yard (shown in the photo above) is at half-mast in protest.

When someone asks, “Who died?” I will respond, “Fifty-five million infants and our Republic.”

God Bless America the Church.

[Contributed by JD Hall]