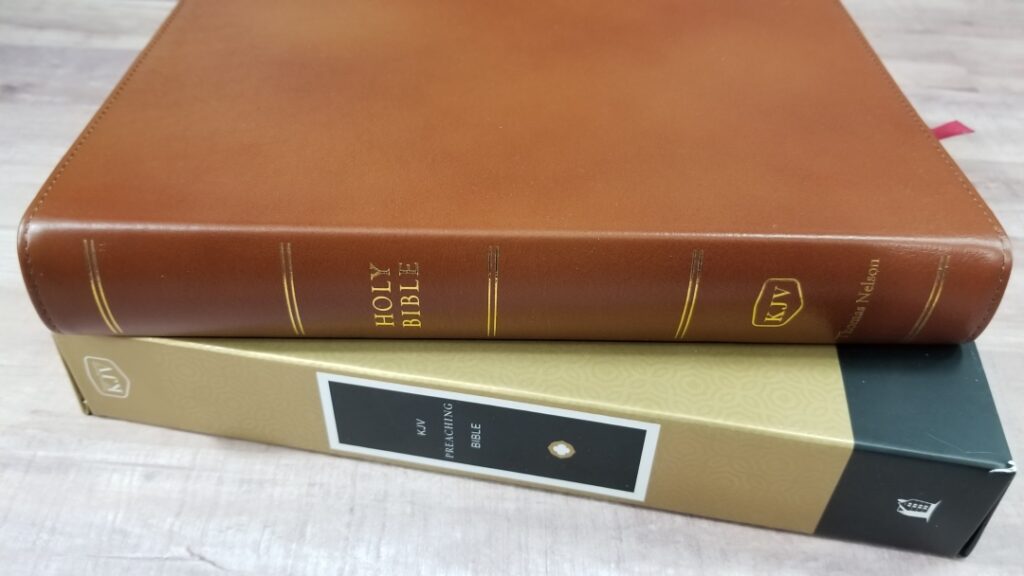

Here are five good reasons why Reformed and Confessional Christians should be using the KJV.

Introduction: What is the “Confessional Text” Position?

The Confessional Text Position is also known by a few other titles: TR advocacy, The Ecclesiastical Text, The Canonical Text, and The Traditional Text. More recently it has been given the title of the Textual Traditionalist Position by internet apologist, James White, and has even been labeled as a form of King James Onlyism in both White’s book on the topic and Dr. Andrew Naselli’s book, “Understanding and Applying the New Testament”. The Confessional Text Position can be defined as: the position that accepts the underlying Hebrew and Greek texts used by the framers of the major post-reformation confessions, which they called “authentic” and “pure”, as the preserved text of the Bible.

There are five main reasons why I, as a Pastor, hold to and advocate for this position.

1.) Theological Reason

My first reason for holding to the Confessional Text Position is because it is founded on theological grounds. Rather than starting with man and his ability to correctly interpret the manuscript evidence, the Confessional Text Position begins with faith in God’s promise to preserve and deliver His word to His people, and not simply to inspire it and leave it to man to assemble the surviving pieces together. The Lord Jesus Christ gave this promise in (Matthew 5:18) “For verily I say unto you, Till heaven and earth pass, one jot or one tittle shall in no wise pass from the law, till all be fulfilled”, and in (Matthew 24:35) “Heaven and earth shall pass away, but my words shall not pass away.” Further, the Apostle Paul tells Timothy in (1Tim. 3:16,17) that, “All scripture is given by inspiration of God, and is profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, for instruction in righteousness: that the man of God may be perfect, throughly furnished unto all good works.”

The Confessional Text Position begins with faith as its starting point; believing, that because Jesus promised that none of His words shall pass away, therefore God will certainly keep His promise and give His word unto His Church, not in part, but in full. The puritan, John Owen (a chief framer of the Savoy Declaration of Faith and attendant at the Westminster Assembly) states, “the Scriptures of the Old and New Testament [which] were immediately and entirely given out by God himself … [are] by his good and merciful providential dispensation … preserved unto us entire in the original languages.” (Works, 16, pp.351,352)

Michael J. Kruger makes a fantastic argument from faith for the Canon of Scripture (which books belong in the Bible) when he says,

“The books received by the church inform our understanding of which books are canonical not because the church is infallible or because it created or constituted the canon, but because the church’s reception of these books is a natural and inevitable outworking of the self-authenticating nature of Scripture” (Canon Revisited, 106)

Kruger argues for a theological method for determining the Canon of Scripture. This means that we are to argue theologically for which books belong in the Bible, rather than from evidence alone. But the Confessional Text Position takes this theological method a step further, applying this faith based starting point, not just to the titles of the books, but also to their contents. As a pastor, I know what a coveted joy it is to own the full 22 volumes of Calvin’s commentaries on the Bible. But if, when I took down the volumes off my shelf, only to find the covers and title pages present, I would not truly be able to say that I possess Calvin’s commentaries, I would simply own the covers. So too, the Bible was inspired, preserved and given to God’s people in the entirety of its content, every jot and tittle, not simply the covers or title pages. The Church not only received the Canon of Scripture, but also its content.

This is exactly what the Irish puritan James Usher said, when asked what reason he had for knowing that the Scriptures are Divinely authored: “The marvelous preservation of the Scriptures [demonstrates this]. Though none in time be so ancient, nor none so much oppugned; yet God hath still by his providence preserved them, and every part of them.” (Body of Divinity, p.8)

So when it comes to examining manuscript evidence, historical evidence, or versional evidence we must start, and remain with, a theological method for determining both canon and text. The puritan Thomas Watson argued for the Divine origin of the Scriptures with this argument: because the Scriptures have been perfectly preserved, they are therefore Divinely authored. He writes,

“We may know the Scripture to be the Word of God by its miraculous preservation in all ages … Nor has the church of God, in all revolutions and changes, kept the Scripture that it should not be lost only, but that it should not be depraved. The letter of Scripture has been preserved, without any corruption, in the original tongue.” (Body of Divinity, pg.19, emphasis added)

For Watson, the Scriptures have come down to us entirely pure, even to their very letter, which is in keeping with Jesus’ words above. This is a theological argument, one which we should take seriously. We know that the Scriptures are of divine origin because they are perfectly preserved, and they are perfectly preserved because they are of divine origin.

2.) Historical Reason

The second reason why I switched from a critical text position (which teaches that we can and still need to reconstruct the Bible from the extant manuscripts) is a historical reason. This is intimately connected with the theological reason, but also distinct. As a Confessionally Reformed Baptist, I subscribe fully to the 1689 London Baptist Confession of Faith. This doesn’t mean that I hold it to be equal with Scripture, but rather, I hold it to be an entirely accurate summation of what the Scriptures teach concerning doctrine and practice. Since I take my confessional subscription seriously, I must therefore hold to what the confession teaches concerning the Scriptures.

It is commonly said in response to this assertion: “the framers of the confession did not say anything about text criticism or editions of the Bible”. This is an understandable conclusion based on most people’s theological starting point concerning the Bible, namely, that the Bible is inspired by God and inerrant, only in the original manuscripts (which no longer exist), and therefore we must seek to reconstruct the original readings like we would any other human book from antiquity (interestingly, the current critical Greek texts are being put together by people who have abandoned the search for the original and are seeking merely for a likely early form of the text). The framers of the confessions were fully aware of the textual variants discussed today, they simply handled them from a theological framework over and above the methods employed today.

The London Baptist Confession of Faith states in Chapter 1.8, “The Old Testament in Hebrew … and the New Testament in Greek … being immediately inspired by God, and by His singular care and providence kept pure in all ages, are therefore authentic.” To understand how this statement (which reads the same in both the Westminster Confession of Faith and the Savoy Declaration of Faith) relates to text criticism, we must understand what the framers of the confessions in the puritan and post-reformation era meant by the “authentic” text. James Usher states that all final authority in doctrinal disputes rests upon the original languages, since they, and not translations (specifically the Latin Vulgate which the Papists held to be authoritative), are the only sources “to be held authentic.” (p.19)

According to the framers of our confession, the “authentic text” is the Hebrew and Greek texts over against any translation. This was specifically aimed at Rome which had stated that because the Hebrew and Greek texts had been corrupted, the preserved Bible was only the Latin Vulgate. So when the confession speaks of the original language texts as being authentic and “kept pure” they are referring, not to a hypothetical original lost to history that must be reconstructed, but to the printed Hebrew and Greek texts in their possession. For the framers of the confessions, the “authentic”, “pure” and “perfectly preserved” texts are the printed editions of the Hebrew OT and the Greek NT then in their possession. The Church in the 16th and 17th centuries, in God’s providence, collated and edited the Hebrew and Greek texts which the people of God possessed, and printed editions of these collations. The men behind our confessions recognized these printed editions of the original language texts as the “authentic” and “pure” text; inspired, preserved and given by God during the reformation, and it is my opinion that we who hold to these confessions should as well.

3.) Evidential Reason

The third reason why I switched from the Critical Text Position to the Confessional Text Position is based on the evidence. Although evidence is not the foundation or the starting point of the Confessional Text Position (but rather, a theological foundation, which states that God has preserved and the Church has received/recognized the text which He inspired), the evidence is in overwhelming support of the traditional texts. I will not be going into detail extensively here (see references for in depth handling), but one example should suffice.

What is often called the “longer end of Mark” (found in Mark 16:9-20) is in most modern translations either relegated to a footnote, or placed in double brackets with a disclaimer. In the ESV, this passage is placed in double brackets with a heading placed in all caps that reads: “SOME OF THE EARLIEST MANUSCRIPTS DO NOT INCLUDE 16:9-20”. It is fairly agreed upon in modern Biblical Scholarship that this passage was not part of the original text of Mark and is not to be considered Scripture, even though it is contained in the reformation era Greek texts and has been utilized by millions of Christians, via translations of those texts, for 500 plus years. The claim is that the “earliest” and “best” manuscripts do not contain it and therefore we should not consider it as Scripture. This sounds fairly convincing and makes it seem somewhat silly that people would still argue that the reformation era texts were correct in viewing the longer ending as Scripture; that is, until you look at the evidence.

When we examine the evidence (starting with the theological method for determining Scripture) we must first turn to Paul to see how he defined a gospel. In 1Corinthians 15:1-6, Paul says that the gospel contains these 5 criteria: Jesus’ death for our sins, His burial, His resurrection, His being seen, and His ascension. So going back to the gospel of Mark, we know that for it to be a valid gospel account, it must possess all 5 criteria.

If we follow the modern text critical scholars and assume that the gospel of Mark ends with v.8, then the gospel ends with the women at the tomb not seeing Jesus, being terrified, saying nothing to anyone, along with no mention of Jesus’ appearance or ascension. If this is the case, then, according to Paul, the Gospel of Mark is not a gospel and the entire book should be rejected as inspired Scripture. On that ground alone we should have a serious problem with accepting the modern critical text.

Furthermore, when we then look at what the manuscript evidence actually is to support the idea that Mark ends at 16:8, we see that this conclusion is based on two extant manuscripts that are only a century earlier than our first surviving manuscript which contains Mark 16:9-20. They give priority to two manuscripts over the 1,000 plus manuscripts which contain Mark 16:9-20. This conclusion is not based on the weight of the evidence, but on the interpretive bias of those examining it.

4.) Personal Reason

My fourth reason for holding to the Confessional Text position is personal. I started learning Greek in 2010 and have since then read from the Greek NT in my daily devotions. For many years, as a critical text advocate, I used the standard modern critical Greek texts (The Nestle-Aland and the UBS). I was made aware of variants and learned how to read the textual apparatus at the bottom of the page, which shows you the variants along with information about them. I began to wonder how I could affirm the inspiration and inerrancy of the Bible if we didn’t have it. The common saying, “We can reconstruct the original with 99% accuracy” began not to cut it anymore for me. If God inspired His word, why didn’t He preserve it? And if He did preserve it, then where is it? Why didn’t God give the Word He inspired and preserved unto His Church?

This led me down a road of questioning everything I believed about the Bible, and because I had been so often told that the Confessional Text Position is traditionalist at best and anti-intellectual at worst, I didn’t believe I could hold it as a tenable position. The only place I found solace, was in the theology of Karl Barth who taught that the Bible was merely a human witness to God’s Word; it was an artifact of the revelation event, and only becomes the Word of God when God makes it so, of His own sovereign grace, to the reader. After struggling in this position for a year, I re-examined the Confessional Text Position, finally began to understand the three reasons for holding to it which I have mentioned above, and found rest and solace knowing that God had given His word to His Church. Now, in my personal life, I no longer question God’s word; I no longer stand in judgement over it with my textual apparatus, but it stands in judgement over me as a saved sinner.

5.) Pastoral Reason

The fifth and last reason I hold to the Confessional Text Position is a pastoral reason. In my sermon preparation I no longer have to spend hours trying to reconstruct the original with textual-commentaries and apparati, I can confidently work from the text God has given and preserved, assured that what I am giving my people comes from the very word of God itself. My church also benefits in my preaching. Their confidence in the word of God is no longer cut down as their pastor explains textual variants during the sermon. They can be confident that the Bible I am preaching from and that they have in their laps, is a translation of the preserved word of God.

In conclusion, I argue that this is the most tenable position to hold to as a Christian in the 21st century and the most agreeable one to the confessions. It is my hope that this article helps you to better understand the Confessional Text Position and fosters confidence for God’s word within you.

MORE READING

https://www.agroschurch.com/blog/a-response-to-dr-james-whites-fatal-flaw-argument-against-the-tr

http://www.jeffriddle.net/2019/08/review-article-posted-garnet-howard.html

http://www.jeffriddle.net/2017/02/word-magazine-69-epistemology-and-text.html

https://www.agroschurch.com/blog/a-basic-understanding-of-the-confessional-text-position

Historical

http://www.jeffriddle.net/2019/08/review-article-posted-garnet-howard.html

http://www.jeffriddle.net/search?q=Confessional+Text

http://www.jeffriddle.net/2017/01/article-erasmus-anecdotes.html

Evidential

http://www.jeffriddle.net/search/label/Ending%20of%20Mark

http://www.jeffriddle.net/2016/02/response-to-ryan-m-reeves-church.html

http://www.jeffriddle.net/2018/07/wm-98-ending-of-mark-syriac-and-metzger.html

https://www.tbsbibles.org/page/articles

Pastoral

https://www.agroschurch.com/blog/four-ways-to-shepherd-your-flock-through-text-criticism-a-response

https://www.agroschurch.com/blog/dr-jeff-riddle-a-small-part-of-a-bigger-picture

Works Cited

All Scripture references come from the KJV

Owen, John. The Works of John Owen. Edited by William H. Goold. Vol. 16. Edinburgh: T&T Clark, n.d.

Ussher, James. A Body of Divinity. Birmingham, AL: Solid Ground Christian Books, 2007

Watson, Thomas. A Body of Divinity. Grand Rapids, MI: Sovereign Grace Publishers, n.d.

[Editor’s Note: Contributed by Dane Jöhannsson, the lead pastor of Agros Reformed Baptist Church. This article does not necessarily reflect the view of Pulpit & Pen, which typically uses the ESV in our citations. It is an issue of growing concern among Reformed Christians, however, and many are taking a second look at the argument presented for using the Textus Receptus. Opposing scholarly viewpoints are encouraged, and may be sent to P&P to be considered for publication on our contact page]