Tom Buck is a friend of mine. We haven’t always been so friendly, but we seem to have made some kind of amends. So then, let me come along and mess up all that peace and harmony by using him as an example of something that is quite annoying to many of us who aspire to be more discerning. And for the record, I told Tom I would be writing this opinion piece and why. Let this first paragraph serve as a disclaimer that I’m only using Tom Buck as a case-in-point, and mean no irreparable harm to his reputation and pray we use it as a learning opportunity.

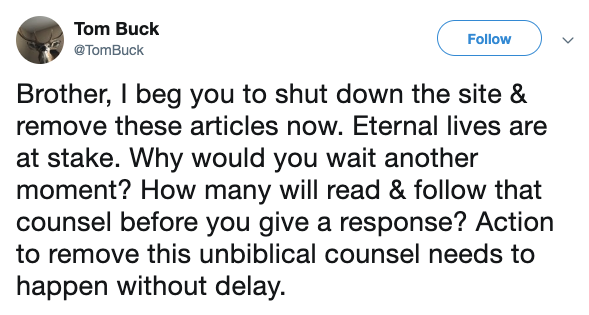

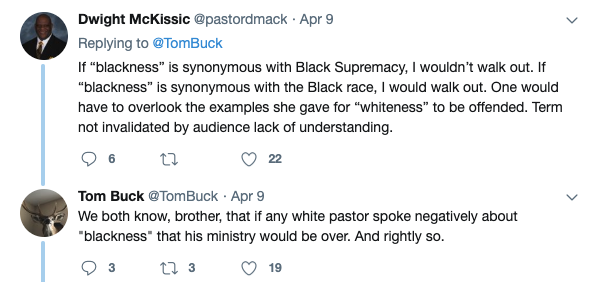

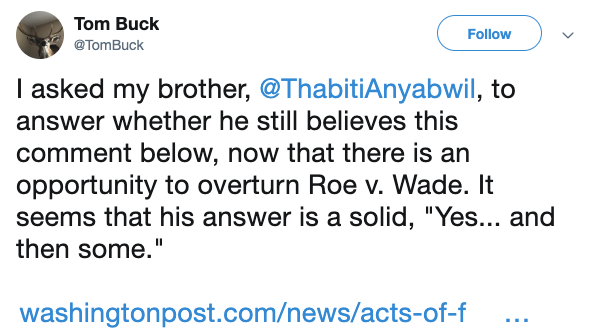

It seems that almost weekly I get emails that contain hand-wringing complaints about Buck’s use of one particular word. Buck uses this word in his social media, and in particular, on Twitter wherein lies most of his public influence, and Buck’s use of this word often concerns people. I agree entirely about their concern.

The word Tom uses that causes so much concern is the word, brother…

Geez. Christians can get mad over anything. Yeah, I know, but hear me out.

There are two different schools of thought regarding use of the term, brother, to people.

The first perspective is that anyone who claims to be a brother-in-Christ should be referred to as such. Only when someone is officially cast outside the church under discipline or who has explicitly been ‘farewelled’ by a sufficiently large chorus of opinion, should we withhold that title of honor (so says this perspective).

In this view, Tom would probably argue that Allberry, McKissic, and Anyabwile all pass a basic Mere Orthodoxy checklist. Because they profess Christ and haven’t explicitly denied any essential Christian doctrines, they should be referred to as a brother.

The second perspective is that the term, brother, is a high honor among Christians and isn’t to be thrown around promiscuously. To toss about the term toward those who are teaching subversive, dangerous, or troubling teaching (or those engaged in subversive, dangerous, or troubling behavior) actually cheapens the honor. It’s like passing out a participation trophy to the fat kids on a losing streak in t-ball; it kind of makes all the awards meaningless.

Those on this side (my side) of the aisle would reserve the term, brother, for those we are either (A) sure aren’t dangerous or at least (B) unaware that they’re dangerous.

When Len Pettis debated Chris Date, who is an annihilationist, I chided Len for insinuating that Date was a brother-in-Christ. When I debated Ante Pavkovic, who is a Montanist, I refused to acknowledge him as a brother-in-Christ (which became a point of contention after the debate). However, I don’t consider New Covenant Theology to be as wicked an evil as I do charismaticism, so when I debated Louis Lyons on the Sabbath, I happily embraced him as a brother-in-Christ.

Receiving the title of brother from me isn’t complicated, and it doesn’t require 100% conformity to my theological beliefs, but it isn’t promiscuous, either. If someone is troubling the church, or if they’re teaching dangerous things, I certainly abstain from using the title.

The reason for withholding the title of brother from dangerous teachers (even those who can pass Mere Orthodoxy checklists) is the Bible’s model. I believe that if Scripture is our guide, we would use the term more cautiously than we commonly see it done by many modern evangelicals who use the word in an unchaste manner.

A few points for our consideration.

First, withholding brother from a troublesome or schismatic teacher isn’t anathematizing them. It’s just exercising caution.

Fred Butler touched on this point in a post at Hip & Thigh back in 2015. The context of his article was my theonomy debate and the ensuing dust-up in which it was common for theonomists to demand that you say whether or not they were a brother-in-Christ. I’ve seen this strategy commonly from sub-Christian sects, including AHA and other groups. If you deny they are brethren, you’re set up as a meany-pants jerk. If you affirm their brotherhood they’ve won a moral victory and ask why you’re ‘attacking’ Christian brothers. It’s a lose-lose situation.

Butler addresses this, writing:

Would the finger-wagging scolds on social media please stop with their insistence that I embrace theonomists as brothers? Their rebukes are both patronizing and phony…

Just so I am clear.

I am not saying, by any stretch of the imagination, that those men who hold to theonomy are unsaved or not Christian.

Again, I AM NOT SAYING THEONOMISTS ARE UNSAVED.

Let me state it one more time, in bold, navy blue font: I AM NOT SAYING THEONOMISTS ARE UNSAVED! (I even added an exclamation point for emphasis).

I will further add that not ALL theonomists are alike with the dishing out of the scornful disdain against me and like-minded critics; but it is the majority perspective I see displayed where I have encountered them.

With those clarifications in mind, let me state up front that I believe theonomy is significant enough of an error, and has become such a major point of division among believers, that I would be hard pressed to lay brotherly, affirming hands upon theonomists and their respective ministries.

Fred’s perspective is that embracing someone enthusiastically and vocally as a brother-in-Christ while they are yet in great theological error is not reasonable and should not be expected (even if they can pass a Mere Orthodoxy Checklist).

My reason for not tossing around the term brother like Snoop Dog ‘making it rain’ at a strip club isn’t because I know someone is for sure lost. It’s because I’m not sure they’re in right standing with God.

Clearly, there are many who have no problem with James White slathering ‘brother’ on Michael Brown like Jan Crouch coated her face with makeup on TBN. But the rest of us hear James do that and we throw up in our mouths a little bit, because we know that Brown is a dangerous and subversive teacher who promotes the worst charismatic charlatans on the planet. I don’t know for sure that Michael Brown is going to hell. But I sure don’t know that Michael Brown is going to Heaven because he’s in a handbasket heading south with the world’s most prominent heretics. Therefore, it would be unwise, unprofitable, and uncouth to embrace a troublesome teacher as a brother-in-Christ out of a sense of ceremonial politeness.

I ask you, who troubles the church more, Michael Brown or Steven Anderson (I would argue that Brown’s influence is much greater and those he promotes – from Benny Hinn to Brian Houston – are actually quite worse than Anderson)? And yet, I doubt that James White would embrace Steven Anderson as a ‘brother-in-Christ’ so readily.

Who’s a bigger threat to evangelicals, Steven Anderson or Sam Allberry? I’m thinking it’s the gay guy who’s fundamentally shifting evangelical sexual ethics. Would Buck embrace Steven Anderson as a Christian brother? I doubt it (but I could be wrong). When we use the term ‘brother’ in reference to popular evangelical teachers, but deny the term to unpopular evangelical teachers, when both happen to be equally as troubling to the church, we become respecters-of-persons and use the term, brother, as a matter of rhetorical strategy. Again, this cheapens the term.

Pavkovic asked me, “Would you consider me a brother in Christ?”

My response was, “I’m not going to use that term towards you.”

He asked in retort, “Are you saying I’m not a brother in Christ, then?”

My response was, “That’s not really my job.”

Ultimately, local churches anathematize people. Withholding the term is not a pronouncement of anathema. It’s just caution.

Second, those who teach grievous errors are never looked at charitably in Apostolic writing. Tom Buck is a sweetheart (sometimes). I’ve known Tom for years and he looks at people far more charitably than I do, and I’ve relished the opportunity to say, ‘I told you so,’ on numerous occasions (Tom first went sideways with P&P in defense of Karen Swallow Prior, but has now called for her resignation from the ERLC, having got ‘woke’ to all things we were telling you back in 2015).

See? I just rubbed that in again. I’m incorrigible.

But the point is, Tom is charitable to a fault. If you’re going to err, I suppose some consider erring on the side of charity to be the moral high ground. On the other hand, I believe that if our chief concern is the flock of God, we would rather err on the side of caution. This is what is reflected in the Bible.

Jude says that subversive teachers “crept in” (secretly and intentionally) and that they were “designated long ago for destruction” (Jude 1:4). That’s a pretty sweeping generalization of false teachers. Did Jude know them all? Did he have personal first-hand knowledge that they were all teaching falsely intentionally? No, of course not. Jude assumed it (and his assumption was Spirit-inspired, so there’s that).

This assumption – that false or subversive teachers are intentionally false and subversive – is common all throughout the Apostolic writings. In 2 Peter 2:1-3, Peter warns that false prophets “secretly introduce destructive heresies” and calls their behavior “depraved.” He assigns them motives of “exploiting you with fabricated stories.”

Again, Peter presumes that the teachers who trouble the church are doing it on purpose, secretly, subversively, intentionally, and that they do not mean well.

Paul also has this guttural distrust and lack of charity toward subversive teachers in Galatians 2:4-5, as he presumes that the Judaizers – who were sent by Pastor James of Jerusalem – came in “secretly, to slip in and spy out” the church, in order to bring it into slavery. The term Paul uses for them is “false brothers” (verse 4), indicating that by subversively sneaking their dangerous doctrines into the church, it was cause enough to call their brotherhood false.

The charitable attitude of the 21st Century, when put through the lens of Scripture, comes out looking less like charity and more like naivety. The Apostles, such as Jude, Peter, and Paul, would have presumed that those teaching subversive and dangerous doctrines know exactly what they’re doing and were being intentionally crafty and subtle because they work for the other team.

Is there any room for charity toward subversive idealogues? Yes! Absolutely! The charity is reserved for their repentance and eventual restoration. In Galatians 6:1, Paul tells the church to restore those caught up in sin (presumably those following the Judaizers) in a spirit of gentleness. The term, ‘caught up in sin,’ implies an awareness of it, and restoration is done willingly. In other words, this spirit of gentleness is reserved for those who are willing and ready to admit their error. For those still teaching error unrepentantly, Paul tells them to emasculate themselves and that they’re cursed.

That word, brother, should not be coerced or demanded as a part of a rhetorical strategy or debate technique. Likewise, the term should not be tossed about willy-nilly out of a sense of misplaced charity.

Instead, the term should be reserved for those with whom we have few reservations.

-JD Hall

[Publisher’s Note: Tom Buck is a nice guy and is being attacked on all sides, left and right. But he’s tough; he can take it]