I will use treatment to help the sick according to my ability and judgment, but never with a view to injury and wrong-doing. Neither will I administer a poison to anybody when asked to do so, nor will I suggest such a course. Similarly I will not give to a woman a pessary to cause abortion.

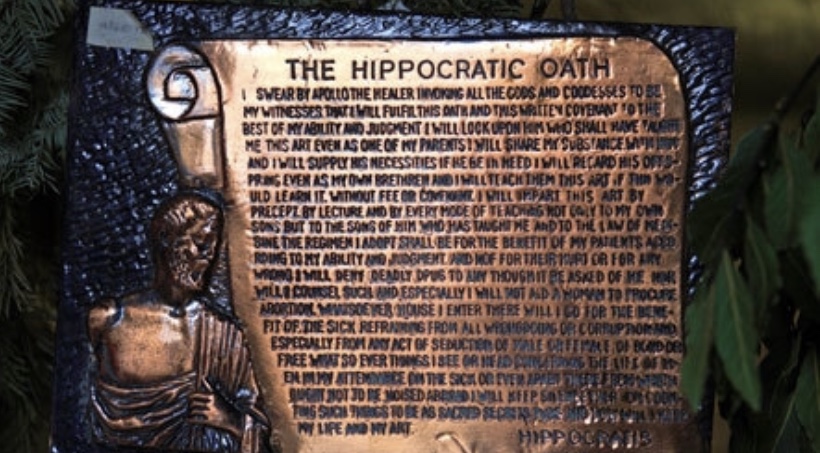

A portion of the earliest surviving version (c. 275 AD) of the Hippocratic Oath.

Over the course of centuries, the Hippocratic Oath has been rewritten to reflect the values of different cultures.

Today, contrary to common belief, most medical schools do not require new physicians to swear the Hippocratic Oath.

Overall, in 2017, approximately 56% of new physicians took the Hippocratic Oath and 17% of new physicians took an oath specifically written by the medical school faculty they attended. Also to note, in America, the oath does not include the above quoted portion.

[Life News] Stephanie Ho’s passionate desire to abort unborn babies is difficult to understand.

It makes sense that the young Arkansas abortionist wants to help women in need, but there are so many better ways to help women than to make a living off killing their unborn children.

Ho recently wrote a piece for the Washington Post about her work with Planned Parenthood, the largest abortion chain in America. In it, she complained about her medical school not teaching abortion, people not accepting her work, abortion regulations and more.

“Where I grew up, in the River Valley of western Arkansas, nobody said the word ‘abortion’ out loud,” she wrote.

Ho chose to attend medical school at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock, and then complained that the school did not teach them how to perform abortions.

“Over four years, the most exposure we got to the topic was a half-hour guest lecture,” she wrote.

Ho continued:

That implicit disapproval carried over to my residency in family medicine, which I began in 2008 at UAMS West in Fort Smith. Second-year residents gave presentations on a topic of their choice — and mine, on abortion, was the most highly attended and contentious that year. A senior faculty member vocally disagreed with my description of abortion as a common medical service, interrupting every few sentences and quoting the Bible at me. Someone dubbed me the “abortion chick,” and the nickname stuck. Whenever a patient at the clinic wanted to learn more about terminating a pregnancy, the staff would call me in to talk her through her options, even when I wasn’t scheduled on a shift. My fellow physicians didn’t feel comfortable sharing information about abortions.

She claimed to have faced even more discrimination during her third-year elective rotation when she wanted to go out of state to learn how to do abortions.

“The residency director said it was not an appropriate elective for a family medicine resident, and that he would have to talk about it with the other faculty physicians at Fort Smith,” she remembered. “Then he said that the program didn’t permit residents to rotate out of state.”

After graduation, she said she could not find anyone willing to hire her in conservative Arkansas because of her insistence making abortion part of her practice. Ho opened her own practice, but it did not go well.

She “lived paycheck to paycheck,” and it eventually failed. That’s when she began working as an abortionist for Planned Parenthood in Arkansas.

“Today, I am one of four physicians regularly providing abortions in Arkansas, which is home to 1.5 million women. Who else is going to speak up for them?” she proudly stated.

“My patients sit through 48-hour waiting periods and mandatory follow-up visits, which impose costs — gas money, time off from work, overnight stays, child care — that many can barely afford,” she continued.

[Editor’s Note: This article was written by Micaiah Bilger and originally published at Life News]