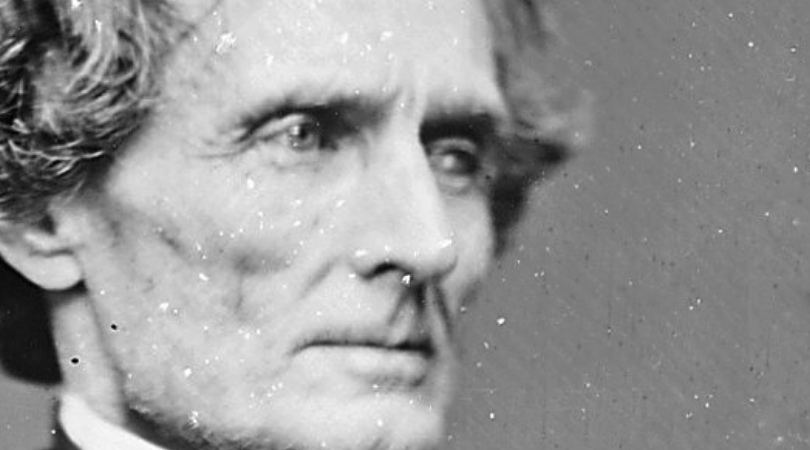

Jefferson Davis was the first – and only – president of the Confederate States of America. Born in 1808 and serving as president of the Confederacy from 1861 to 1865, Davis was a member of the Democratic Party and after the end of the Civil War encouraged the defeated South to

Although Davis is

Race-based and generational slavery, a clear and wicked evil, was simply perceived by many of Davis’ day (wrongly so) to be a responsibility of stewardship for the upper classes. Davis thought it a responsibility to care for those who he was convinced were unable to care for themselves (wrongly so). Although by our standards, Davis was an incorrigible racist, by the standards of his time he was an enlightened and open-minded liberal and far more sympathetic to the plight of the slaves than Abraham Lincoln, who was famously indifferent to their suffering. In fact, after his capture, his bail was paid by abolitionists in the North.

Even more significant to Davis was his conviction that slavery was constitutional and within the rights of the individual states to make laws criminalizing or legalizing the practice, which ultimately led Davis to pick the losing side of the Civil War.

Beyond the complexities of states’ rights and the nuances of antebellum slavery, Jefferson Davis was a man of deep and admirable Christian faith.

The Constitution of the Confederate States of America, under the guidance of Davis, named the fledgling nation a uniquely Christian country, “invoking the favor and guidance of Almighty God.” The language used therein provoked Benjamin Morgan Palmer, the pastor of the First Presbyterian Church of New Orleans, to call it “a truly Christian patriot’s prayer” and by comparison made the U.S. Constitution look like “perilous atheism.”

Davis then called for the nation’s first religious fast on June 13, 1861, petitioning its Citizens to seek God’s face in repentance and supplication. Davis chose the Latin phrase, Deo Vindice (“With God as our defender”), for the national motto.

Davis appealed to God’s divine providence in his inauguration address:

I enter upon the duties of the office to which I have been chosen with the hope that the beginning of our career as a Confederacy may not be obstructed by hostile opposition to our enjoyment of the separate existence and independence we have asserted, and which, with the blessing of Providence, we intend to maintain.

Davis’ conversion seems to have come after the war began. Although he had been “God fearing” and steered the confederacy to give God a place of honor in their founding documents and traditions, Davis professed Christ first publicly in 1862. After being ‘baptized’ in the Episcopal church, Davis’ frequent citations of Scripture became even more common.

After his capture, Davis’ jail physician wrote the following in his journal:

There was no affection of devoutness of asceticism in my patient; but every opportunity I had of seeing him, convinced me more deeply of his sincere religious convictions. He was fond of referring to passages of Scripture, comparing text with text, dwelling on the divine beauty of the imagery, and the wonderful adaption of the whole to every conceivable phase and stage of human life. The Psalms were his favorite portion of the Word, and had always been. … There were moments, while speaking on religious subjects, in which Mr. Davis impressed me more than any professor of Christianity I have ever heard. There was a vital earnestness in his discourse, a clear, almost passionate, grasp in his faith; and the thought would frequently recur, that a belief capable of consoling such sorrows as his, possessed, and thereby evidenced, a reality – a substance – which no sophistry of the infidel could discredit.1

source link

Sadly, the Episcopalian Church in Alabama where Davis attended for three months before the Confederate C

Although Davis has been vilified and largely forgotten as a democratically elected president within what is today the United States, entirely due to his position on slavery, the reality is that we will one day – most likely – see Brother Davis in Heaven.

It is less likely that we will see Abraham Lincoln in glory, who is widely regarded as a skeptic and atheist for having never been a member or even attended a church and having said, “I have never united myself to any church because I have found difficulty in giving my assent without mental reservation to the long complicated statements of Christian doctrine which characterize their articles of belief and confessions of faith” (July 11, 1860). Although sometimes using religious language in campaign speeches, the best Lincoln biographers regard him as an unbeliever. This cannot be said for his counterpart, Jefferson Davis.

Imagine a world where being wrong on racism doesn’t make someone eternally condemned before God and where being right on racism doesn’t make one eternally justified. That’s the world of both Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis.