(RNS) — Snake-handling Pentecostals may be on the fringe of American religious culture, but a new opera brings their exuberant worship and rockabilly-inspired music to center stage this week.

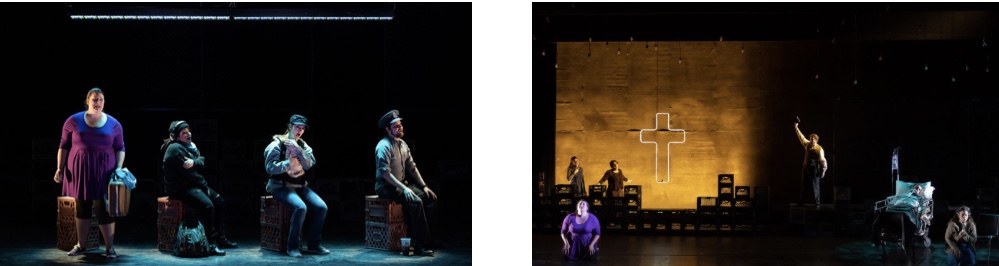

“Taking Up Serpents,” a 60-minute work by composer Kamala Sankaram and librettist Jerre Dye, debuts Jan. 11 and 13 at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C.

Set in Gulf Shores, Ala., the opera tells the story of Kayla, a 25-year-old clerk in a convenience store whose father runs a serpent-handling church. Washington National Opera soprano Alexandria Shiner plays the lead role. Timothy J. Bruno plays her father, the pastor of a Pentecostal congregation called the “Church of the Lord Jesus Christ With Signs Foretold.”

The “signs” referred to in the church’s name come from Mark 16:17-18, which claims believers can speak in tongues, survive a dose of poison or a bite from a venomous snake, heal the sick and cast out demons. Most Pentecostal churches accept the first, fourth and fifth signs as normative. But only about 100 U.S. congregations, mainly in Appalachia, believe that church services should also include snake handling and the quaffing of strychnine and similar poisonous substances.

The opera traces Kayla’s journey after she learns her father is dying of a rattlesnake bite in a Birmingham hospital. Her mother wants her to come home. As she travels there, Kayla reminisces over her childhood and frayed relationships with her family. She visits her father in the hospital, then makes her way to his church.

There won’t be any live snakes onstage, but during the final aria, Kayla reaches into a snake box (typically a flat wooden box with a Plexiglas cover) to pick up a serpent.

“She does choose to handle at the end,” said Dye, who grew up Pentecostal and embraced “gifts” of the Holy Spirit such as speaking in tongues. Although his family didn’t frequent serpent-handling churches, he knew they existed nearby.

“When I grew up, snake handling was considered the line in the sand for that culture,” he said. “The most theatrical charismatics would absolutely distance themselves from snake handling. They would say, ‘We don’t handle snakes, but we know people who do.’”

The opera was inspired by Dye’s upbringing and the 1995 book “Salvation on Sand Mountain,” which features serpent handlers in Alabama’s rural northeast. He calls serpent handlers one of the great hidden stories of the South. Their church services, he said, are filled with built-in drama.

“Possessing an electric testimony is built into the culture,” he said. “They have to talk about how God found them. They call themselves godly and yet their lives are very messy.”

Dye was also impressed with the music of serpent handlers, which is often improvised and plays a major role in church services. Congregants will sing and dance for hours during worship.

“There’s a jangly, gorgeous lopsided sound to their music. It’s like Johnny Cash crashes into something,” Dye said. “They’re all very self-taught and they use piano, tambourine, drums, whatever instruments are available.”

Dye has left the beliefs of his childhood behind. Theater, he said, has taken the place of religion in his heart. Still, there are the memories.

“I try to tell this human story of this search, this longing,” he said.

The use of snakes in worship services is a solely American phenomenon, beginning around 1910 after George Hensley, a preacher from Chattanooga, Tenn., began teaching that the Mark 16 verses mandated the practice. The practice spread to the point that several states in the region outlawed serpent handling because of the many deaths that resulted.

About 100 people have died of snake bite or poison intake during such services over the last century. One of the most recent deaths occurred Feb. 15, 2014. The Rev. Jamie Coots, 42, the co-star of “Snake Salvation,” a 2013 reality show on serpent handling aired by the National Geographic Channel, was fatally bitten while holding three rattlesnakes at a church service in Middlesboro, Ky.

Serpent handling is not a practice associated with the arts world, as it’s typically represented in documentaries or photo exhibits. As for fiction, Ralph Hood, a psychology professor at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga who’s considered the world expert on the practice, said there had been a few novels about the snake handlers, although “none of any real merit,” he added.

Robert Ainsley, director of the American Opera Initiative program sponsoring “Taking Up Serpents,” said religion is not an alien theme for opera.

“‘Samson and Delilah’ have huge elements of that,” he said. “This opera is more about a dysfunctional family than about serpent handling, but religion is fundamental to the plot. Faith is a constant and a given and it flows in some form through everyone’s life. I think that (Dye) has nailed that fact.”

The performance, which has a cast of six (playing multiple characters) and a 13-piece orchestra, heads up a quartet of short operas sponsored by the American Opera Initiative Festival. The festival, which seeks to bring new talent for the opera stage, commissions pieces that reflect American society.

Sankaram, the composer, had worked with music in Episcopal and Catholic settings but wasn’t familiar with immersive music that dominates in Appalachia. Because the freewheeling rockabilly style of serpent-handling churches was foreign to her, she watched a lot of videos to get a feel for the four- to five-hour services. The music typically includes bluesy keyboards, electric guitars, drums and tambourines.

[Editor’s Note: This article was written by Julia Duin and originally published at Religious News Service]