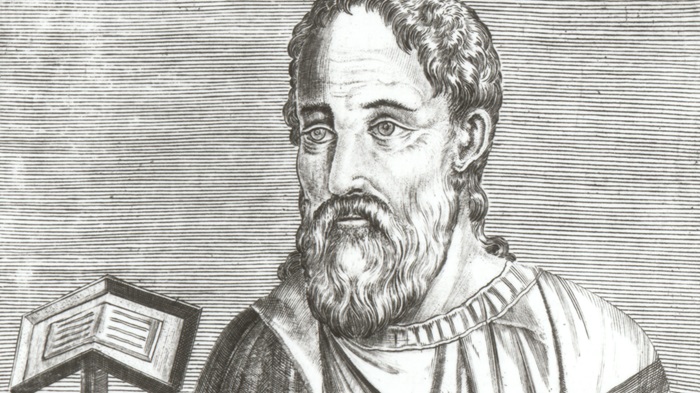

Eusebius of Caesarea is one of my favorite early church leaders. He was a historian, Biblical scholar, and polemicist. He became a pastor in Caesarea in about 314AD. He produced works like Demonstrations of the Gospel, Preparations for the Gospel, and On Discrepancies between the Gospels, all of them brilliant studies of the Biblical text. Eusebius is known as “the Father of Church History,” and wrote Ecclesiastical History, On the Life of Pamphilus, the Chronicle and On the Martyrs. One of my most favorite things about Eusebius is his work against the charismatic-Montanists, who he despised.

To be clear, Eusebius was not perfect in his theology. He was a student of Lucian of Antioch – as was Arius – and this gave him sympathies to Arius and reluctance to denounce Arius as a heretic. Eusebius was a reluctant signer to the Council of Nicaea and had to be chastened and disciplined before finally renouncing Arianism (he later tried to claim Arianism was compatible with the Council of Nicaea, and had to eventually recant that as well). His personal relationship with Arius seemed to blind him a bit.

However, Eusebius is a valuable resource for the church on multiple fronts. Firstly, he is the preeminent historian of the early church and there were none finer. Secondly, Eusebius wrote – as a pastor – with fine theological precision when explaining the history of the early church. He was no outsider-looking-in, like the earlier historian Josephus. Eusebius was a believer writing history for other believers, and so his work gives us brilliant incite into the feelings of the early church.

What did Eusebius – and by extension, other Christian leaders – think about icons, or images, of God the Father, Son or Holy Spirit? Whether or not these images were worshiped, what did Eusebius and others think about their creation? Were such images acceptable or unacceptable to early Christians?

Eusebius, being the prominent Christian leader that he was, had a relationship with the half-sister of Emperor Constantine, Constantia Augustus. She had written Eusebius and asked for an image of Jesus. Eusebius flipped out, explained that such a request was tragically blasphemous, and rebuked her heavily for it. That letter between Eusebius and Constantia is not preserved in full, but it was important enough that sections of the letter were actually discussed at the all-important Council of Nicaea (which was preserved), as well as preserved in certain other places. All the existing excerpts of that letter were put together by Joseph Boivin and included in the notes section of his work, “Nicephorus Gregora’s History,” which was written in 1702 (there is a version to the entire work on Google Books, and is available here).

George Florovsky of S. Vladmir’s Seminary in New York wrote on this topic in Origen, Eusebius and the Iconoclastic Controversy an even greater book on church history. He writes:

It was a reply to Constantia Augustus, a sister of Constantine. She had asked Eusebius to send her an ‘image of Christ.’ He was astonished. What kind of image did she mean? Nor could he understand why she could want one. Was it a true and unchangeable image, which would be true to Christ’s character? Or was it the image he would have assumed when he took it upon himself, for our sake, the form of a servant? The first, Eusebius remarks, is obviously inaccessible to man; only the Father knows the Son. The form of a servant, which had be amalgamated with his divinity…obviously, this splendour cannot be depicted by lifeless colors and shades. If even in his flesh there was such a power, what is to be said of him now when he had been transformed the form of a servant into Lord and God? Now he rests in the unfathomable bosom of the Father. His previous form has been transfigured and transformed into that splendor ineffable that passes the measure of any eye or ear…we cannot follow the example of pagan artists that cannot be depicted and can therefore have no genuine likeness. Thus, the only available image just an image in the state of humiliation. Yet, all such images are formally prohibited in the Law, nor are any such known in the churches. If we want to anticipate this glorious image, before we must meet him face to face, there is but one good painter, the Word of God Himself…the main point of this is clear…Christians do not need any artificial image of Christ. They are not permitted to go back; they must look forward. Christ’s “historical” image, the “form” of its humiliation, has been already superceded by his divine splendor, in which he now abides [emphasis mine – look at pages 85-86 in the book, hyperlinked above].

Eusebius rebuked the living daylights out of the Empress (bold of him), and told her that only heretics make pictures of their leaders, using Simon Magus and Mani as examples of this. He told her that she should be content with the divine Logos written upon her heart, and not have an image of Jesus (source link).

There are only a few translations of these excerpts from Eusebius’ stinging rebuke to Empress Constantia, and they’re all stuck behind pay walls of scholastic journals (I paid $42 for one earlier today, but that does not give me the liberty to share it). Most of its pertinent parts can be found in PDFs online, and especially the modern miracle of Google Books, which is a feat of cyber engineering that is keeping old books from going completely extinct. In fact, you can read more about Eusebius’ letter (complete with excerpts) to Constantia here and many other places.

For a wider treatment of why Eusebius believed that all icons were to be forbidden, here’s an interesting synopsis of the topic from the Center for Hellenic Studies at Harvard University. Even aside from the Second Commandment that forbids images of God, Eusebius also denies the validity of such images on Platonic grounds (so goes the theory) that a replication always “waters down” the real. No doubt, coming from a land flush with idols would make any Christian think twice about crafting graven images of God, whether or not they were intended to be worshiped.

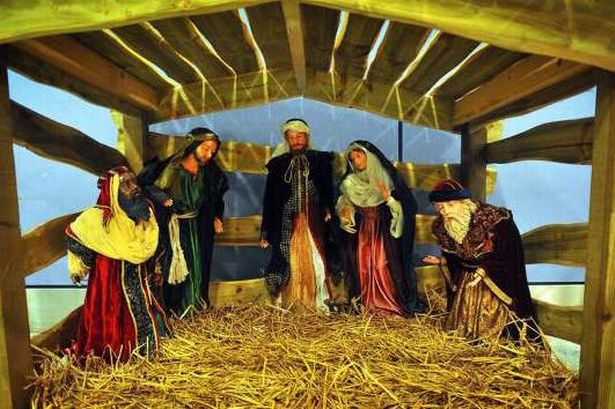

You can read more about this topic at our first installment for this series, “Should You Display a Nativity Set This Christmas,” here.

[Contributed by JD Hall]

- Christmas Series: Should You Display a Nativity Set this Christmas? Part I.

- Christmas Series: Are Nativity Sets Biblical II? The Opinion of Eusebius

- Christmas Series: Are Nativity Sets Biblical III? The Opinion of John Calvin

- Christmas Series: Are Nativity Sets Biblical Part IV…The 5 Worst Nativity Sets (Maybe)

- Christmas Series: Are Nativity Sets Biblical? Part V, Francis Turretin