I’m more annoyed at myself than anyone else, really. There’s no decent reason to be giving an anonymous-pseudonymous social media account the time of day, let alone using a few minutes of my hunting-day to provide a defense to the incessant goading and belligerence by one known as “Turretin Fan.” Most anonymous-pseudonymous social media accounts are operated by people with a range of deep-seeded issues, ranging from sociopathy to cowardice – with colorful backstories behind every one. Even Batman has a reason to wear a mask, I guess. There just seem to be a lot of batmen out there today.

“Turretin Fan,” as he calls himself, has been antagonistically tagging me on Facebook along with a few theonomists who also disagree (weird, I know) with the common misconception among the American populace that Obergfell v Hodges created a “law” that Kim Davis is guilty of violating. Chiefly, I’ve written or spoken about the subject here, here, here, here, here, here and probably more places if you cared to look. I’ve agreed with Bryan Fischer and others, who assert that opinions of a court are not “law” in American jurisprudence. That such an assertion would be scandalous or scurrilous speaks to the condition that 60 years of jettisoning civics education in the public school system has left us.

Faulty governmental worldview:

Before I explain why a court ruling is not the same as “law” in this constitutional republic, and before I move on to explain why solids are not liquids in an important forthcoming post, let me lay out what may be a genuine worldview difference that has led to certain miscommunication.

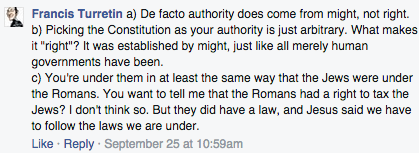

First, what I see Turretin Fan (henceforth TF) do, is cite from dictionaries the meaning of “law.” I believe the fundamental worldview difference is that TF believes (so it seems) that the status quo ante bellum is de facto law. In other words, TF believes that what is treated as law after the civil war, is indeed, law. The status quo is not status quo ab initio – the state of affairs from the beginning. What is, in our imaginations, is not necessarily what is in reality. Things may be treated as law, but it does not mean they are, indeed, law. I believe TF would disagree with that assertion from the outset.

Secondly, TF doesn’t seem to believe in a government of constituted principles, forged in written or documented laws. Disagreeing with my assertion that “might doesn’t make right” in our social media interaction, TF claimed that

De facto authority in this nation, much to TF’s disagreement, does not come from might. That statement alone is an assault upon our constitutional republic and the principles upon which our actual de facto authority rest – that we are a nation of laws. Since the Magna Carta came to America with its earliest settlers, authority on this continent has been vested in laws and not in might (source link). Created in 1215, denying that simple premise of the Magna Carta is a an 800 year step backward in civil government.

No freemen shall be taken or imprisoned or disseised or exiled or in any way destroyed, nor will we go upon him nor send upon him, except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land. – Magna Carta (1215, Article 34)

Our laws, from the earliest days of our Republic, were prefaced upon that concept of civil governance, that might does not make right. What is – in reality – is what should be. What was designed to be, is. However twisted or tyrannical the status quo has become, is irrespective of what the laws of governance truly are. Our earliest leaders recognized the fact that authority is vested in law and not might.

“There is no good government but what is republican. The very definition of a republic is an empire of laws, and not of men.” – John Adams

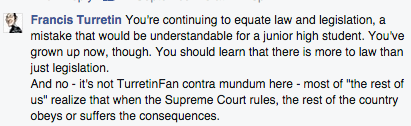

And yet, when presented with the notion that our nation is designed with three branches of government and only one is given the authority by law to make law, TF clearly exhibited a sentiment foreign to western, civilized jurisprudence.

“When the Supreme Court rules, the rest of the country obeys or suffers the consequences.” – TF

TF’s draconian decree that when the Supreme Court rules, the country must “obey or suffer the consequences” is in stark opposition to not only the three-branch separation of powers first articulated by John Locke and written into the American constitution, but does violence to the entire system of checks and balances upon which our government has been founded. Our founders recognized the possibility of a tyrannical judiciary and firmly opposed it. In fact, one of the primary drafters of the Constitution, Thomas Jefferson, said that such judicial tyranny would be the same as the Republic committing a felo de se (felony against self), IE to commit suicide.

The Constitution, on this hypothesis (that the judiciary is the last resort in relation to other branches of government), is a mere thing of wax in the hands of the judiciary, which they may twist and shape into any form they may please. It should be remembered, as an axiom of eternal truth in politics, that whatever power in any government is independent, is absolute also; in theory only, at first, while the spirit of the people is up, but in practice, as fast as that relaxes. Independence can be trusted nowhere but with the people in mass. They are inherently independent of all but moral law. – Thomas Jefferson, letter to Judge Spencer Roane (1819).

Our nation’s history is rife with examples of the legislative or executive branches rejecting the judiciary’s opinion in their submission to We The People and in their charge of checking and balancing the judiciary’s power. In Worcester v Georgia, which laid out an arguably unconstitutional edict giving sovereignty to “domestic, dependent nations” (aka Native American tribes) as a way to keep states from dealing officially with tribes independently of the federal government (as a historical caveat, the federal government needed to recategorize Native American tribes as sovereign nations so that states could not make their only treaties and policies regarding them, which amounted to a power-grab of the federal government). Recognizing the potential unconstitutionality of Worcester v Georgia and the courts being used as a political instrument to usurp state’s rights, President Jackson said famously of the court led by chief justice, John Marshall, “John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it!” A fuller quotation from Jackson is as follows…

“…the decision of the Supreme Court has fell still born, and they find that they cannot coerce Georgia to yield to its mandate” – Andrew Jackson, in his letter to John Marshall

In other words, “Thank you for your opinion, judiciary, but the executive branch and the state of Georgia will not be enforcing it.” While Jackson’s dismissal of court opinion would (probably) not have sat well with Madison, it would have with Jefferson, as the two founders felt slightly differently on the subject. Their disagreement aside, this is just one instance among countless others of the executive or legislative branches – as a part of their job description – not letting the judiciary become tyrannical.

Judicial Review:

Does the Supreme Court have the right of judicial review? And if so, what does that mean?

Judicial review is the basic notion that the judiciary’s job, in part, is to review the decisions and actions of the executive and legislative branches. Almost all would acknowledge that this is the purview of the Supreme Court. The question is what does “review” mean? We’ll revisit that question in a moment.

Judicial review is not something we see written explicitly into the constitution, although I’m comfortable believing it is implicit (as opposed to explicit) because of the wealth of information regarding what the founders meant and desired, present in the Federalist Papers and Anti-Federalist Papers. We’ll revisit that in a moment, also. But first, the concept is taken (again, implicitly) from Article 3, Section 3, Clause 2:

In all cases affecting ambassadors, other public ministers and consuls, and those in which a state shall be party, the Supreme Court shall have original jurisdiction. In all the other cases before mentioned, the Supreme Court shall have appellate jurisdiction, both as to law and fact, with such exceptions, and under such regulations as the Congress shall make.

You can see why, “Where exactly does the Constitution entitle the courts to “force” their decisions upon the executive or legislative branches” is a legitimate question. Yeah. Where exactly?

Rather than being explicitly constitutional, judicial review entered first into the American legal tradition (emphasis on tradition) in the 1803 case, Marbury v Madison. Essentially, President Adams made a number of judge appointments, but then-secretary of state, John Marshall, neglected to commission those judges, a formality – but a necessary, required one. As President Jefferson took office, then-secretary of state, John Marshall, became Supreme Court chief justice. Jefferson refused to let his secretary of state, Madison, commission those Adams appointed and Marshall neglected in his official responsibilities to commission, and those judges – including Marbury – took Madison to court over the issue. The court ruled in favor of Marbury, and that surprised no one. The notion of judicial review was no surprise and neither was it controversial. However, Marbury desired the court to issue a Writ of Mandamus, essentially ordering Jefferson to follow the court’s decision – or else (which is essentially what Kim Davis received, prior to her unlawful imprisonment). In a victory for checks and balances, Marshall refused to issue that decree because it was not the judiciary’s right to do so – and although the court’s opinion was heard on Marbury v Madison and Jefferson was scolded by Marshall, Marbury did not receive his commission because the judiciary could issue opinions but not tell the executive branch what to do.

Marshall’s actions fell precisely in line with the opinion of Alexander Hamilton, who advocated for judicial review in the Federalist Papers, but did not want “review” to mean “enforcement.”

A constitution is, in fact, and must be regarded by the judges, as a fundamental law. It therefore belongs to them to ascertain its meaning, as well as the meaning of any particular act proceeding from the legislative body. If there should happen to be an irreconcilable variance between the two, that which has the superior obligation and validity ought, of course, to be preferred; or, in other words, the Constitution ought to be preferred to the statute, the intention of the people to the intention of their agents.

Nor does this conclusion by any means suppose a superiority of the judicial to the legislative power. It only supposes that the power of the people is superior to both; and that where the will of the legislature, declared in its statutes, stands in opposition to that of the people, declared in the Constitution, the judges ought to be governed by the latter rather than the former. – Federalist Papers, #78

Clearly, judicial review does not entitle the judiciary to “boss around” other branches of government and certainly not – as Hamilton points out – entitle them to boss around We The People.

American Jurisprudence

TF pointed to several definitions of “law” he had taken from various dictionaries (here and here ) to counteract my assertion that laws are passed by legislatures and not decreed by the judiciary. In this post, he also gives as a defense “common law” and “case law” (which we’ll come back to).

What a “law” is in American jurisprudence is not determined by dictionaries, but by law – and that is, chiefly, the United States Constitution. Any overt attempt by liberal non-constructionists to claim the courts make law or policy is usually met with derision – for good reason. When Sonia Sotomayor made a comment to Duke University in 2005 that courts “are where policy is made” it almost scuttled her appointment to the Supreme Court. That’s because almost anyone, besides judges and attorneys who desire more political power, recognize that notion (one TF supports) to be constitutionally fallacious. Of course, Sotomayor has gone on to unconstitutionally create policy, in court decisions relating to ObamaCare, Obergfell v Hodges, and countless others.

Constitutionally, it’s a no-brainer.

“All Legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Senate and House of Representatives.” Article 1, Section 1 of the United States Constitution

Maybe, for those without a civics education, they should click on “How Laws are Made” on the House.gov website. The branch of government directly controlled by the people (remember – neither the president nor the supreme court is popularly elected) is to be the sole creator and rescinder of law (source link). Even the executive’s right to veto can be overridden by We The People. Any system in which law is created by those not directly controlled by We The People makes America cease to be a nation by the people, for the people. In fact, the only right of law nullification of any party at the table of American government belongs not to the executive or judicial branches, but to We The People directly through the jury nullification of law. A jury of 9 Citizens has more power to overturn law (in case-specific rulings) than 9 Supreme Court justices.

This is why when (hopefully soon ousted) Mitch McConnell, Senate Majority leader, said that “The SCOTUS decision on gay marriage is the law of the land and there’s nothing we can do about it,” it brought so much outrage from constitutional conservatives who realize that he – as a legislator – is in more of a position to “do something about it” than almost anyone. Chiefly, the legislature can simply ignore the decision altogether and tell the court, “Thank you for your opinion.” McConnell and other senators and representatives could robustly and boldly defend the standing United States law on gay marriage, which is the Defense of Marriage Act. To fight to have DOMA passed into law, and then to not provide any check or balance to the judiciary who unconstitutionally attempts to “strike down” that law, is the heart of cowardice and ignorance regarding his own job description.

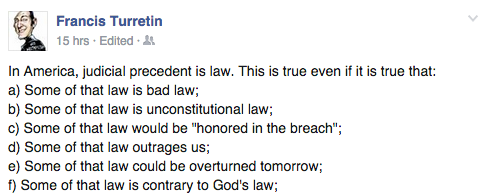

Regarding common law (or so-called “case law”), as TF desperately gave as examples of laws not passed through the legislative branch, I really have no need to provide much defense. While common law is created (and serves the purpose of) creating broad consistency in judgment, using previous court rulings as a standard for future rulings, there is no inkling in American jurisprudence that courts or legislatures or the executive branch of government is somehow obligated to obey case law or common law in the carrying out of their fiduciary responsibilities.

Whereas “case law” (or judicial precedent) is indeed a “thing” (and its name is unfortunate and deficient) it does not supercede statutory, or legislated law. Stare decisis, or precedent, in the common law understanding, is on the same level of authority as “regulatory law” (another unfortunate title), or rules passed down by regulatory agencies of the government (in British common law, Stare decisis is sometimes considered on par with statutory law, but in American common law, it is not – but only on par with regulatory “law”).* The idea that a precedent cannot be ignored is tied closely with the idea of a super stare decisis (a term coined by Richard Posner and William Landes in 1976) – which is a completely imaginary, asinine notion that some precedents are so important the create de facto law. The chief example of super precedent is Roe v Wade, and because enough people – like TF – have equated precedent with law, abortion is believed to be “the law of the land” based off of a court opinion. That idea may be status quo, but it is not status quo ab initio and neither is it reality. It’s a falsehood that’s been believed to be reality, and strict constructionists deny repudiate the idea with vigor.

The real danger is when there are enough individuals without a civics education to believe that stare decisis transcends statua legis (statuatory, written, legislated law).

Conclusion: TF said that I need to consult my attorney friends before advocating my position that American law is created by legislatures. Really, I don’t. I don’t need to consult those who are within the realm of the judiciary and expect them to limit their own power within the American political system. And frankly, we don’t need more attorneys. We need more Citizens to carry around in their pocket the US Constitution (for a free pocket-constitution, click here) and to have a basic familiarity with American jurisprudence. I would suggest finding some quality homeschool material on American civics and take the time to bring yourself up to an elementary understanding of how laws are created and the branches of government divided.